ARCH REVIEW | Making Complicity

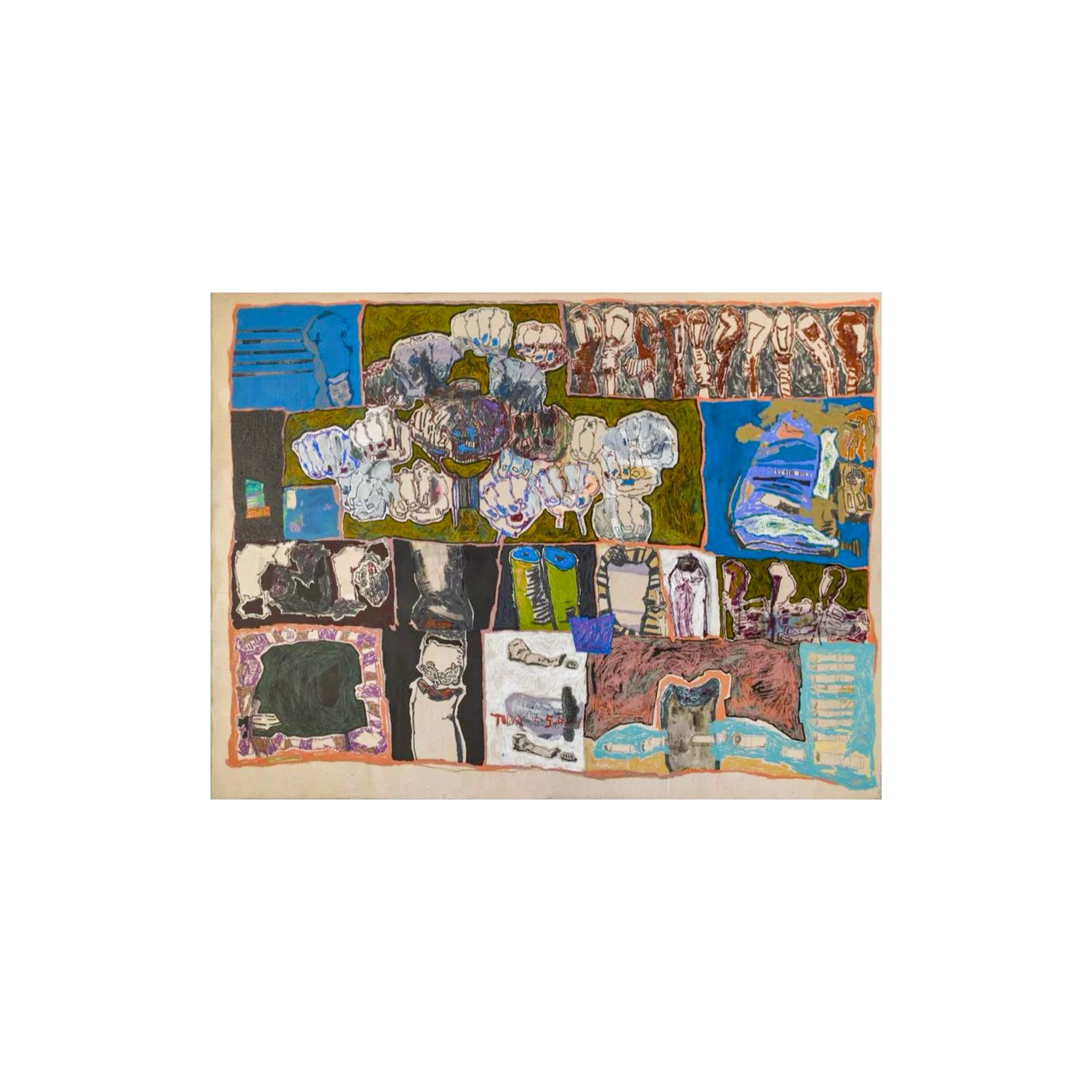

Making Complicity

Artist: Guo Yujian

Text by Liu Guangli

- Dangerous Complicity, ©ARCH GALLERY 2022

- Dangerous Complicity, ©ARCH GALLERY 2022

When the painting is really close to us, the first thing that appears to our eyes is this Le cimetière marin[1] written by Valéry in 1922. The curators Hu Yihang and Zhang Tingzhi, together with artist Guo Yujian, divided the exhibition “Dangerous Complicity” in the gallery into three chapters with words and symbols: imagination, a plateau, and a theatre. Whether intentional or not, the passage selected at the beginning is contented with poet Valéry’s deep nostalgia for his hometown of Sète. As he wrote in correspondence with the writer Gide[2]: “When I am upset, when the waves of life push me back to the geometric point of wanting to be a child, there is always an image of the sea in my mind, where I have ran out the last breath of my life. Then my presence merged with the vast ocean , and I felt as a whole within it. “[3] After Valéry’s death, he was buried in the seaside cemetery in his hometown. For Guo Yujian, this may be a coincidence after he finished study abroad in Italy, he resolutely returned to his hometown Changsha to create.

- Dangerous Complicity, ©ARCH GALLERY 2022

- Dangerous Complicity, ©ARCH GALLERY 2022

In the new works exhibited in this show, we can always observe the images appearing in pairs, or tearing the outline of a certain part of the painting, or fading away in the colour blocks, there seems to be some kind of non-narrative ambition here: Painting has to wrest the image from the “figurative”. “Not to represent what can be seen, but to make things visible.” But that’s easier said than done, even Bacon[5] said: “However, the story that told between one image and another removes the possibility of painting acting through itself from the very beginning. There is a great difficulty here.”[6] Deleuze described the predicament in this way when commenting on Bacon’s painting: “Between two images, there is always a story slips in, or tries to slip in, to bring life into the graphical representation. So isolation is the simplest technique, the essential, though not sufficient, to break with representation, to break the narrative, to hinder the graphical appearance, thereby liberating the image: sticking only to the fact of painting.”[7] Deleuze called this “possibility of a non-diagrammatic, non-narrative, and even non-logical relationship” between the images “the indisputable fact” .

- Dangerous Complicity, ©ARCH GALLERY 2022

Because of this, Guo Yujian’s paintings always show a different kind of generative rhythm, as if the picture is just fixed at the moment when the image is about to become a “fact”, but from another direction of movement, the dense brush and pigment can also be understood as a kind of dissipation, if we compare his earlier works, this “dissipation” works on many levels, more refined colours, more chaotic compositions and less definable personal tastes. As Deleuze mentioned, the painter never works with a blank canvas, “on the surface of the canvas there are already potentially various fragmentary images that must be broken with”, “what the painter does is not to fill a white space, but to clean it, sweep it, and clear it.” Excellent painters are always consciously or unintentionally fighting with the cliché that are already on the canvas before they start their brushwork, and with their own aesthetic and skills, the artist struggle to avoid intellectual, over-abstract responses to stereotyped images, and to bring kitsch back from the ashes.

- Dangerous Complicity, ©ARCH GALLERY 2022

- Dangerous Complicity, ©ARCH GALLERY 2022

- Dangerous Complicity, ©ARCH GALLERY 2022

When looking at Guo Yujian’s paintings a few years ago, I wrote: “When I stare at the painting, they stares at me.” This wonderful aesthetic experience of “being thought about by things” in his new series of works gradually complicated. Random but calmly manipulated brushstrokes, vague but incomparably precise images, tightly wrap the viewer’s wandering gaze, and at the same time make their judgment as a part of the work. The text fragments and symbols placed by the artist in the exhibition space are not so much a supplement nor explanation to the painting as an aesthetic “disturbance”, the artist did not intend to let the audience “understand” the painting , feeling comes first, not intellectual resonance.

- Velvet 2, Oil on canva, 20x20cm, 2022

- Velvet 3, Oil on canva, 20x20cm, 2022

- Velvet 4, Oil on canva, 20x20cm, 2022

The word “dangerous” in “Dangerous Complicity”, in my understanding, first points to the artist’s creative behaviour. Creation is an extreme experience, it is what Baudelaire[8] said “the terrifying cry of the artist at the moment of being defeated”, it is Van Gogh[9]’s note “My sanity is half melted”, is Cezanne’s[10] “abyss” or “disaster”. The second layer of danger is hidden in the “outside” of the artworks. We can borrow the concept of “parergon” mentioned by Derrida[11] in “The Truth in Painting”. The so-called parer is not the edge or frame of the work, but can be understood as an appendage outside the work. Within the framework of the exhibition, the text fragments like chapter introductions, the space framed by the painted walls, the musical scores projected on the walls, and even the small drafts in the preparation stage of the works can be counted in this category. For Derrida, the fringe belongs both to the work and not to the work, on the edge of something that is neither inside nor outside. In Guo Yujian’s exhibition, the delicate details conspired by the artist and the curator are composing and deconstructing the works at the same time. They are not only the painter’s brushwork and gestures, but also the dangerous cracks that the painter deliberately tore open. The logic of (logos), understanding suspended, faculties wandering.

- Dangerous Complicity, ©ARCH GALLERY 2022

At this point, this text has also become the border of “Dangerous Complicity”, and it is unintentional and unable to become the interpretation of the exhibition. As for the truth of the painting, to paraphrase Cezanne’s famous performative words (and also the origin of the title of Derrida’s “Truth in Painting”): “I owe you the truth in painting, and I will tell you.” The truth of “debt” may not be able to be expressed in our words after all, but the painter will take his life as the measurements and slowly fulfil his promise in his strokes.

[1] Paul Valery,1871-1945

[2] The Graveyard by the Sea, poem by Paul Valéry, written in French as “Le Cimetière marin” and published in 1922 in the collection Charmes

[3] André Gide,1869-1951

[4] Andre Gide-Paul Valery: correspondence, 1890-1942. Self-portraits, the Gide : Valery letters, 1890-1942

[5] Francis Bacon,1909-1992

[6] Interviews with Francis Bacon, David Sylvester CBE

[7] Francis Bacon: Logique de la sensation, Paris: Editions de la difference, Gilles Deleuze, 1981

[8] Charles Baudelaire,1821-1867

[9] Vincent van Gogh,1853-1890

[10] Paul Cézanne,1839-1906

[11] Jacques Derrida,1930-2004